In humans, because of our ability to treat diseases, we have transformed Darwinian evolution, or survival of the fittest genetically, to social evolution, which is survival of the fittest group within a society. Nations evolve as a group, those nations that cooperate internally are among the greatest competitors internationally. Ironically those countries that were based on the grand ideas of community sharing, i.e. communism, ultimately failed or are failing, because of cheating, i.e. within group social selection, which is the bane of group selection. In that system, some individuals cheat, end up preying on that society, and become very rich at the expense of the commoner. In such a society the idea of shared community good soon breaks down. Similarly companies with the greatest internal dynamics, associated with cooperation and collaboration, are the survivors. Survival of the strongest individuals in a society (company or nation) leads to predatory behavior, loss of a community goal, and ultimately failure.

The idea that people should be bred for desirable characteristics, like farm animals, has a long pedigree. Darwin’s theory wasn’t required–after all, it was Darwin who relied upon animal breeding practices to explain how nature plays the same role as the farmer. Nevertheless, some of the most famous people who followed in Darwin’s footsteps, including Francis Galton and Ronald Fisher, were unabashed eugenicists. Even Darwin conceded that people could be bred for desirable characteristics and counselled against it only because it would violate our moral instincts, which he regarded as the most distinctive product of human evolution.

Almost everyone who thought about eugenics at that time unquestionably assumed that creating a better society was a matter of selecting the most able individuals, or “hereditary genius”, as Galton put it. Against this background, consider an experiment conducted in the 1990’s by William M. Muir, Professor of Animal Sciences at Purdue University. The purpose of the experiment was to increase the egg-laying productivity of hens. The hens were housed in cages with nine hens per cage. Very simply, the most productive hen from each cage was selected to breed the next generation of hens.

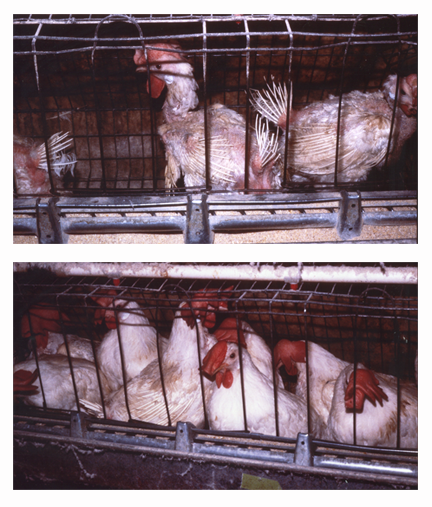

If egg-laying productivity is a heritable trait, then the experiment should produce a strain of better egg layers, but that’s not what happened. Instead, the experiment produced a strain of hyper-aggressive hens, as shown in the first photograph. There are only three hens because the other six were murdered and the survivors have plucked each other in their incessant attacks. Egg productivity plummeted, even though the best egg-layers had been selected each and every generation.

The reason for this perverse outcome is easy to understand, at least in retrospect. The most productive hen in each cage was the biggest bully, who achieved her productivity by suppressing the productivity of the other hens. Bullying behavior is a heritable trait, and several generations were sufficient to produce a strain of psychopaths.

In a parallel experiment, Muir monitored the productivity of the cages and selected all of the hens from the best cages to breed the next generation of hens. The result of that experiment is shown in the second photograph. All nine hens are alive and fully feathered. Egg productivity increased 160% in only a few generations, an almost unheard of response to artificial selection in animal breeding experiments.

Muir’s experiments reveal a tremendous naiveté in the idea that creating a good society is merely a matter of selecting the “best” individuals. A good society requires members working together to create what cannot be produced alone, or at least to refrain from exploiting each other. Human societies approach this ideal to varying degrees, but there is always an element of unfairness that results in some profiting at the expense of others. If these individuals are allowed to breed, and if their profiteering ways are heritable, then selecting the “best” individuals will cause a cooperative society to collapse.

Muir’s experiments also challenge what it means for a trait to be regarded as an individual trait. If by “individual trait” we mean a trait that can be measured in an individual, then egg productivity in hens qualifies. You just count the number of eggs that emerge from the hind end of a hen. If by “individual trait” we mean the process that resulted in the trait, then egg productivity in hens does not qualify. Instead, it is a social trait that depends not only on the properties of the individual hen but also on the properties of the hen’s social environment.

Ever since Muir’s experiments were published, we use them to illustrate the concept of multilevel selection and as a parable for thinking about human social evolution. However, their implications for animal breeding practices are important in their own right. Very few domestic animals are housed as individuals. This means that selection for bullying traits might be taking place even when it isn’t intended, resulting in decreased productivity from the human perspective and increased suffering from the animal perspective. Parenthetically, plant breeders face a similar problem. A corn plant that produces big ears by suppressing the productivity of its neighbors is little different than a hen that produces many eggs by bullying her cage mates.

Professor Muir later added the following:

Genetic evolution had not taken place, of course, but something else had that led to the same outcome. That “something” was the selection and cultural transmission of practices in behaviorally flexible individuals.

I am very happy to have this opportunity to share what I have learned about breeding in a social setting and those linkages to the human situation. We can learn much from animals. While we no longer evolve genetically, we have the intellect to evolve socially and should take the lessons learned from genetic evolution and apply them to society for social evolution to advance. Multi-level selection is powerful, but requires safeguards to prevent cheating and breakdowns of that path. Ironically, between group (company) selection based on capitalism is the only way to keep the system honest. In a capitalistic society, those groups (companies) where cooperation fails will soon be out of business. This process is social selection at the group (company) level. The trust me attitude of an autocratic socialistic society cannot provide adequate safeguards to allow social evolution to keep evolving. As with genetic selection, there can be no evolution without failure, i.e. survival of the fittest groups means that some groups must fail, and be allowed to fail, such that new groups can be formed to continue the process.